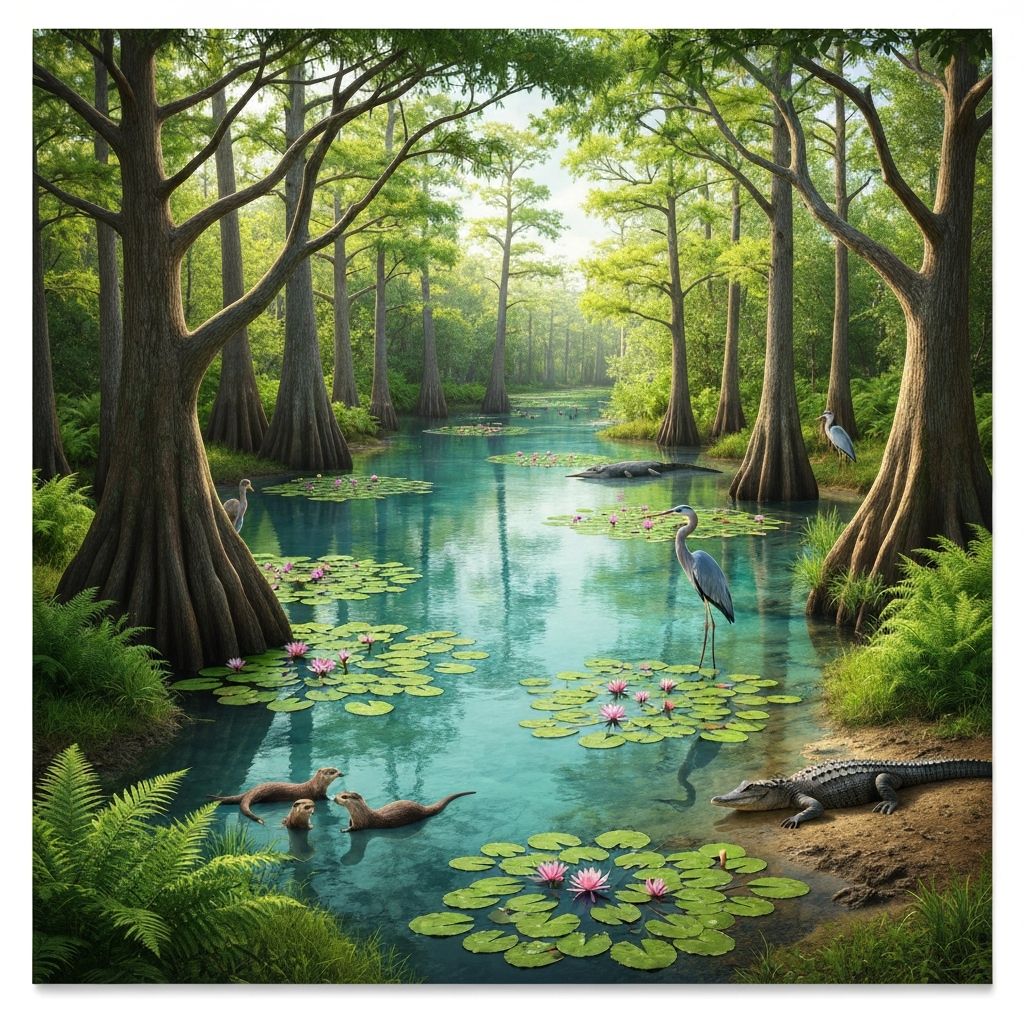

Water Quality & Ecosystem Health

Natural rivers filter water, support biodiversity, and adapt to change. Artificial reservoirs require constant management and can exacerbate pollution problems.

The Water Quality Challenge

Florida's waters face unprecedented challenges. Algae blooms are worsening in the St. Johns River and Indian River Lagoon. Submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) is declining. Nutrient pollution from stormwater, agriculture, and wastewater continues to degrade our waterways.

Both supporters and opponents of Rodman Dam agree that water quality is declining. The question is whether maintaining an artificial reservoir helps or hinders long-term ecosystem health.

The evidence suggests that while reservoirs can temporarily store some nutrients, they don't solve the root causes of pollution. Natural rivers with healthy wetlands and riparian zones provide superior long-term filtration.

Water Quality: Myth vs. Fact

Examining claims about the reservoir's impact on water quality

Myth: "Rodman filters water and improves clarity"

While reservoirs can have a settling basin effect, this is not the same as solving systemic nutrient pollution. The root problems are watershed-wide inputs from stormwater, wastewater, and agriculture. A reservoir doesn't eliminate nutrients—it temporarily stores them.

Fact: Research shows that phosphorus can be retained in some reservoirs under specific conditions. However, this doesn't address watershed-wide pollution sources or provide long-term ecosystem resilience. Natural river systems with healthy riparian zones and wetlands provide superior filtration without requiring constant management.

Myth: "Removing the dam will cause decades of nutrient pollution and algae blooms"

This claim assumes unmanaged, instantaneous removal. In reality, restoration would be phased with careful monitoring. Short-term pulses are a legitimate concern—which is why studies, monitoring, and adaptive management are essential parts of any restoration plan.

Fact: Water already moves from Rodman into the St. Johns through drawdowns and releases. The key question is short-term management vs. long-term ecosystem health. A self-maintaining natural river is ultimately more resilient than an aging reservoir requiring perpetual intervention.

Myth: "Algae blooms are caused by removal, not the reservoir"

Algae blooms are driven by watershed-wide nutrient inputs combined with warm water, low light penetration, and slow-moving conditions—all of which can be exacerbated in reservoirs. The St. Johns River already experiences blooms; attributing them solely to potential restoration ignores systemic pollution sources.

Fact: Natural rivers with adequate flow can help reduce bloom severity by preventing stagnation, supporting SAV that filters water, and maintaining healthier dissolved oxygen levels. The focus should be on watershed-wide nutrient reduction, not preserving artificial impoundments.

Submerged Aquatic Vegetation (SAV)

However, SAV requires sunlight to grow. When water is dark from tannins (naturally-occurring organic compounds from vegetation decay) or turbid from sediment and algae, light can't penetrate deep enough to support healthy SAV beds.

Both reservoir and river systems face SAV challenges. The question is which system—natural or managed—provides better conditions for long-term SAV recovery. Evidence suggests that flowing rivers with healthy riparian buffers support more resilient ecosystems.

Tannins vs. Algae

Algae blooms, however, are driven by excess nutrients (nitrogen and phosphorus) and indicate ecosystem imbalance. Dense algae blocks light, depletes oxygen, and harms water quality far more than natural tannins.

Natural rivers balance tannins with flow and seasonal variation. Stagnant reservoirs can amplify both tannin accumulation and algae growth, creating compounding light limitation problems.

Hurricane Irma's Impact

This demonstrates how major disturbances affect both reservoir and river systems. The question is recovery trajectory: Does a natural system rebound better than a managed one?

Natural Systems Are More Resilient

The debate isn't about whether we can instantly solve all water quality problems by removing one dam. It's about choosing between a managed, artificial system that requires constant intervention versus a natural, self-maintaining river ecosystem that can adapt and recover over time.

A restored Ocklawaha River would support natural filtration through wetlands and riparian zones, reduce stagnation that fuels algae blooms, and create a more resilient watershed for future generations.

Important context: Water quality challenges exist throughout Florida. No single action will solve systemic pollution. But choosing restoration over perpetual reservoir management gives the ecosystem the best chance for long-term health. Short-term transitions require monitoring and adaptive strategies—which is why careful planning and phased implementation matter.

Support Natural Water Quality

Healthier ecosystems start with natural river systems. Add your voice to the call for Rodman Dam removal.

Want to verify these claims? View our sources and references